| 1

IDENTIFICATION OF THE PROBLEM |

If a child is to develop normally , certain conditions must apply

and his/her essential needs must be met.

Growth and development are ,

therefore excellent criteria for evaluating the child’s state of

health and well-being.

The child’s growth and development should be:

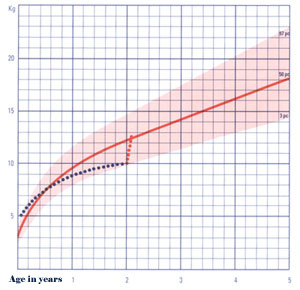

1. Close to the mean value , between limits (for age) within

which 95% of healthy reference children are found. When one

says a measurement is on the 50th percentile (50 pc), this

means that 50% of children of the same age in the reference

population measure more than that amount (e.g. taller or heavier)

and 50% are below (e.g. shorter or lighter).

If a measurement is on the 97 th percentile , this means that 97% of

children in the reference population fall below this level, and 3%

are above. Conversely , a measure on the 3 rd percentile will be

below the values for 97% of normal children of the same age and

above those for only 3% of normal children.

2.

Progressing at a normal rate: a curve

is normal only if it is similar (parallel) to the normal percentile

curve. If , for example , the weight curve crosses the percentile

curve downwards (see figure 1,.) , a cause must be sought (e.g.

malnutrition ,chronic disease); if , no the other hand , it rises

more rapidly than the percentile curve (see figure 1.), this may

indicate , for example , a “catch-up” growth after a period of

illness or malnutrition , or oedema from any cause , or developing

obesity.

|

3.

Without any substantial discordance

between the various aspects of development (e.g. weight,

height and sexual maturation ).The child’s psychomotor

and intellectual development can be evaluated by many

tests of which we will give only a few examples.

As for physical growth, these parameters can be compared with those from

a healthy reference population of the same age.

|

|

Fig.1-Growth curve

(weight-for-age); example of abnormal growth.

·

The standards most commonly used for

evaluating physical growth are those of the National Center

for Health Statistics (NCHS) , derived from studies of a large

number of children of different races in the United States. They are

recommended by WHD.

·

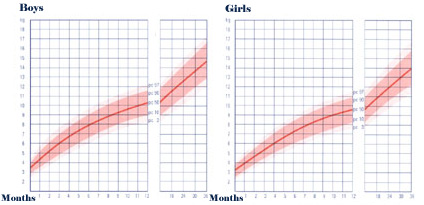

Weight (Fig.2): an easy

measurement to make with a few elementary precautions (child naked,

balance tared). The significance of weight-for-age is , itself , of

limited value , but the rate of weight gain (the growth rate) is a

very sensitive index of good health.

N.B. : when a child is weighed , check

that there is no oedema (see also malnutrition

and glomerulo-nephritis) , which affects the measurement.

Fig.2-Weight-for-age.

·

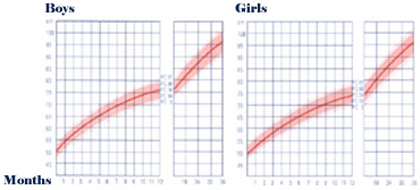

Height (Fig. 3) : This

measurement demands more care and precision than weight , but still

represents “good health” when it is adequate. Height develops too

slowly for it to be an efficient indicator of acute malnutrition.

However , it is a good index of chronic conditions (manutrition

or disease); it is also a good index of the general state of health

of populations. Growth rate varies according to the different

periods of a child’s life. It is maximal in the first five months,

then declines and later goes through a “ spurt” at adolescence. The

growth rate slows during acute or chronic episodes of malnutrition

or disease; precise and closely spaced measurements of height allow

the demonstration of periods of slowing and acceleration.

The measurement of supine height (length) requires an accurate

measuring board and two helpers; standing height can be measured

after 24 months of age, needs only one helper and is about 10-30 mm

less than supine height.

· Weight/height

ratio: the ratio of these two measurements can help

assess “wasting” and give reasonable indication

of growth independent of age, for example when age is difficult or

impossible to determine precisely.

·

The wasting diagram (Fig.4) is

a way of expressing the weight/height ratio which allows one to

detect wasted children quickly. Each column is marked with a weight

, with three colored areas in the upper part. These show the

relation between the child’s weight-for-height and the standard

weight-for-height (NCHS standards). The child stands against the

chart in front of the column representing his weight. The color

shows the degree of wasting. “Very wasted” children are

detected by red; yellow indicates “wasted” , and green

shows normal weight-for-height(90-110% of the NCHS standard).

Fig. 3-Height-for-age

|

Fig.4-Weight-for-height ratio (P.J.Lamotto ,(Documents

Scientifiques Guigoz N 126, 1989) |

|

·

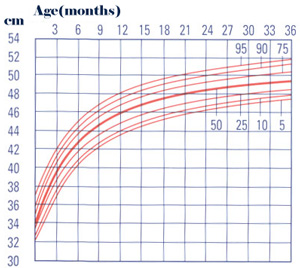

Head circumference

(Fig.5) is an easy measurement to take (maximum circumference), may

reflect the development of the brain and can help with the diagnosis

or monitoring of neurological conditions.

·

Arm circumference: to be

measured on the left arm. It can be used to help assess nutritional

state and muscle mass. It is quite stable (14-16 cm) between 1 and 5

years of age (Table 1).

·

Arm circumference/head

circumference ratio:a quick and helpful index of

nutritional state which is independent of age and sex and which is

useful between the ages of 1 and 5 years:

|

Ratio = <0. 25 severe

protein-energy

malnutrition;

> 0. 25 - < 0. 32 moderate

protein-energy

malnutrition;

> =0. 32 normal.

·

growth retardation in the absence

of severe malnutrition or chronic disease requires detailed

investigation in depth, for which the child should be REFERRED.

|

Fig. 5-Head circumference for age

Fig. 5-Head circumference for age

(Adapted from the NCHS standards) |

Table-Arm circumference (cm)

| |

Boys |

Girls |

| |

5pc |

50pc |

95pc |

5pc |

50pc |

95pc |

| 1 to 2 years 2 to 3

years

3 to 4 years

4 to 5 years |

14.2

14.1

15.0

14.9 |

15.9 16.2

16.7

17.1 |

18.3 18.5

19.0

19.2 |

13.8 14.2

14.3

14.9 |

15.6 16.0

16.7

16.9 |

17.7 18.4

18.9

19.1 |

| 4

PSYCHOMOTOR DEVELOPMENT |

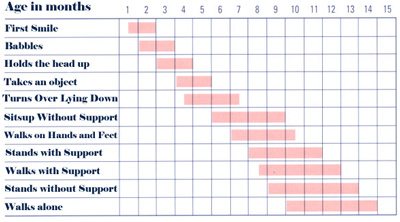

This includes motor development, i.e. development of tone and

prehension movement and stages in the development of affect and

social relationship, i.e. all that which concerns relations with

others (adults and children), and the acquisition of language. The

same stages are always followed, usually in the same order. It is

helped by close contact between mother and child and by the family

environment. The process of weaning , the birth of another child and

separation from the mother may retard this aspect of development.

The neonate shows truncal hypotonia,hypertonia of the limbs and primitive

reflexes; the child progressively acquires truncal tone, which

permits it to:

·

hold up its head at months;

·

maintain a sitting position between 6

and 8 months;

·

walk on hands and feet at about 8-9

months;

· stand upright at 9-10 months;

·

walk at about 1-2 years of age.

These different milestones are passed progressively (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6- Important stages in psychomotor development.

Between 9 and 12 months, the child also begins to hold objects between

thumb and forefinger, and speaks its first words. Sphincter control

begins between 15 and 18 months; at this time , the child can say

several words and combines two words to from short phrases. After 2

years of age, he becomes clean day and night; language becomes more

elaborate with complete phrases.

Certain warning signs should alert the mother and the observer:

·

a child who does not play, is not

interested in his surroundings and sleeps a great deal;

·

a child who is restless and cries

without reason, and who does not sleep at night;

·

a child who makes no or only slow

progress. When this occurs , one should take a history and make a

complete examination; if it is confirmed that there is psychomotor

retardation, REFER for diagnosis and management.

|